October 2024

Lewisham Arthouse, London

Our collective perceives trust in information systems as eroded to the point that everything that we think we know, must be set aside and new foundations for knowledge put in place.

For our next show, we set about building a new ‘library’ from the ground up, each artist bringing with us a collection of research materials to share with the group that acts as the raw materials from which another artist responds.

By making new works in response to each other’s research; we place emphasis on trust and sharing real information through enquiry, challenge individualism in the art world, and commit to remaining critical and playful in the face of polarisation and division in the post-truth era..

Photography J.O. Adamson

The following images are ordered in a way that you will encounter a research box first, followed by the artwork another collective member made egaging with themes from the box.

Susan askew’s research box

The device of ‘The Museum of Human Violence’ highlights ‘fictioning’ as a method for decolonising thinking about nonhumans. Works focus on defamiliarising or ‘making strange’ our fundamental understanding that structures our ways of thinking about the nonhuman.

Askew’s research for this work has more recently shifted to explore ideas about ‘epistemic violence’: that is the ways that knowledge itself is violent. Both the production of academic ‘scientific’ knowledge, and its use, objectify and exploit the ‘other’. Dinesh Wadiwel relates the concept of ‘Epistemic violence’ to the nonhuman. The term originated with Gayatri Spivak who uses it to describe the silencing of people in Colonised nations.

Carmen van huisstede’s response

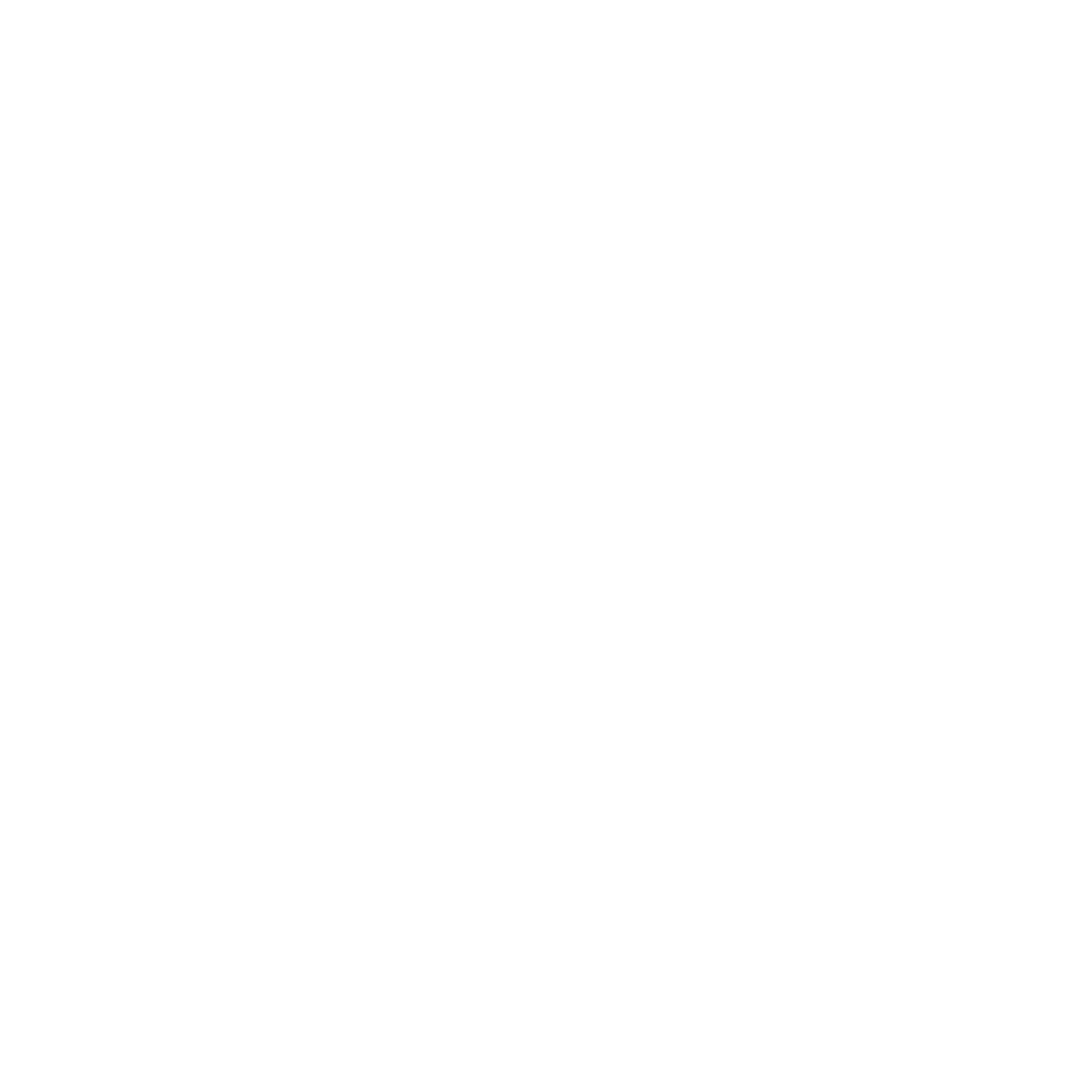

Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy

Carmen Van Huisstede

2024, mixed media installation

47x37x153cm

In this artwork, Carmen presents a fictional scenario where chickens live in an opulent age, highlighting the intersections of surveillance, luxury, and exploitation. The cage’s mirrored floors and ceiling amplify visibility, with cameras capturing and livestreaming every movement. A red light, known to benefit chicks by reducing stress, pecking, and cannibalism, bathes the space, contrasting the underlying themes of control and power.

In her examination of epistemic violence, Carmen employs the metaphor of the cage and the non-human to emphasise how structural knowledge systems create epistemic justice, where one system is elevated over another. This mirrors themes in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, where power dynamics shape hierarchies of truth and knowledge. Carmen’s work aims to investigate the methods through which certain knowledge systems – and their carriers – are systematically erased, annihilated, or destroyed, ultimately leading to their irreversible loss.

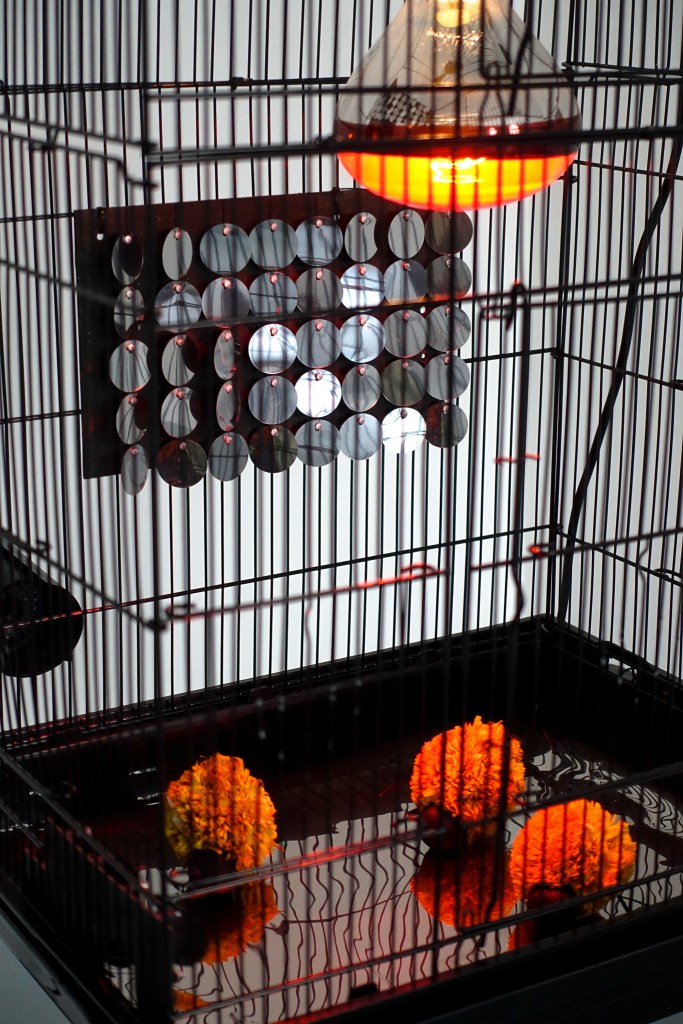

StevieRay latham’s research box

From 19th Century French Realist paintings through to lectures by prominent sciencefiction writers, this collection of research looks at the interconnected web of ideas surrounding class and cultural memory. Stemming from a critical exploration into the perceived veracity of archival photography, Latham’s practice looks to rural folk traditions as an alternative source of social history, decolonised from the perceived historic value of the educated classes. From this perspective, his work questions how sciencefiction tropes of android workforces can be subverted in order to imagine futures for working class communities.

Susan askew’s response

Tryptch. ‘Christ’s Entry into London’

Nasus Y Ram

2065, Ink, charcoal, pencil, collage, biro, pastel and gouache on blue Magnani and Clairefontaine paper

Each 56 x 78 cm

In this work, commissioned by the Museum of Human Violence in 2065, Ram remembers the peace marches across the world in 2036, and draws inspiration from the painting by James Ensor Christ’s entry into Brussels 1889. Ram said In an interview: “Ensor’s imagining of Christ entering Brussels seemed a perfect start from which to reimagine the spiritual enlightenment humans experienced after the Giant Rupture. Human hearts were turned from stone to flesh. The peace in which we now live with all species is miraculous. The timing of events is important to the Museum, and the work refers to temporality in different ways, including the use of traditional drawing methods (blue paper, pencil, collage); non linear curation; past, current and future events.”

Jane hughes’ research box

Jane’s box is a bricolage made from a Victorian chest, a clock face, wire mesh and a discreet painting hidden on the underside. It is crudely constructed, with its internal dimensions constrained to make it harder to extract the copper, canvas, paper, material and film hidden within. For Jane this box a place of fear, secrets and desires, of things hidden, compartments and containers. It represents an assemblage of the ideas and research she has worked on over the last few years around authority and truth mediated through photography and film. It is an archive where alternative stories of those who have been obscured, invisible or absent from history can be contained and explored.

StevieRay latham’s response

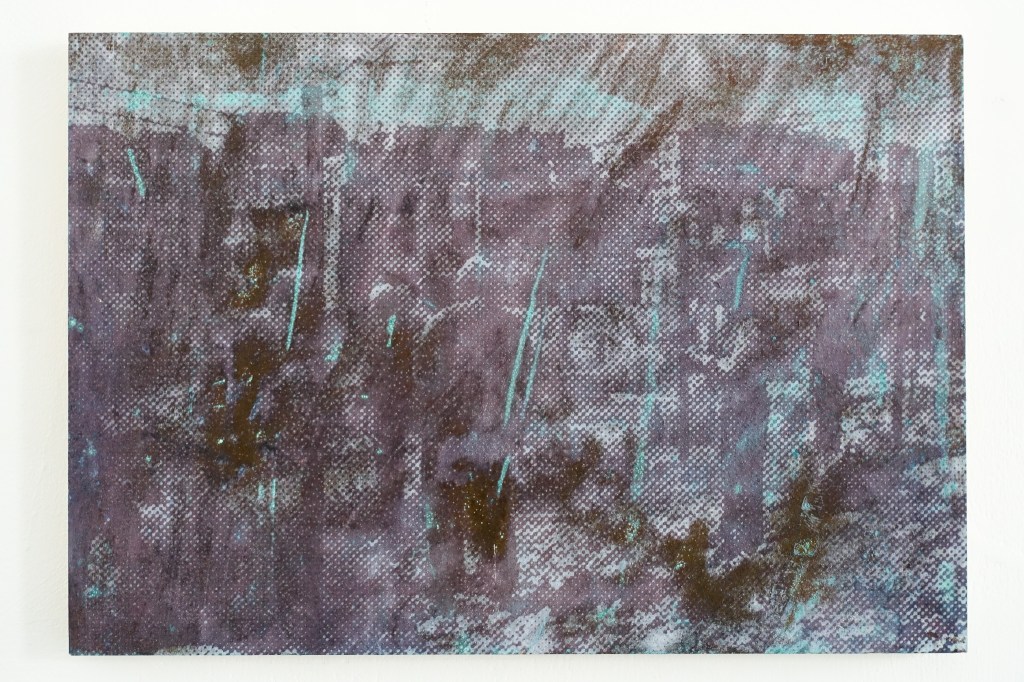

Baucis, Ersilia, Zirma

StevieRay Latham

2024, Ink and salt on copper on board

Each 29 x 42cm

Inspired by the 1972 novel Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, passages from the book are fed into an A.I. image generator and the resulting images are printed onto copper and sprayed with a solution that accelerates the oxidation of the metal. Through this layered approach, the images become obscured and veiled by the patina of the copper, suggesting the fallibility of memory and the archive in the age of post-internet atemporality. Interested in Calvino’s post-modern, imaginary travelogue as an atemporal critique of capitalism, modernism and the rapid urbanisation of the author’s coeval world, Latham finds parallels within his own practice where folk traditions, science-fiction and working class archives regularly become vectors for a discussion about class histories and futures; who is remembered and who is forgotten?

Eleanor street’s research box

Eleanor Street’s practice explores landscape the traces we leave in it and the memories, experiences and objects that we take with us. The research contained within this box investigates presentation of information and the ways in which it can affect our understanding and experience. Using traditional and varied forms of repositories of information – books, maps, film – the research examines the extent to which the full picture is revealed, concealed or fragmented by the manner and method of its communication.

Jane hughes’s response

Dirty Work

Jane Hughes

2024, photo transfer, ink and charcoal

187×93 cm paper

Exploring landscape as an expression of visual appropriation, particularity and marked by inequalities of power Jane utilises the concept of the school chart, established as a system of understanding the world, to challenge rooted notions of order and knowledge. Current conventional discourse implies that the withdrawal of colonial powers has allowed the global economy to function as a meritocracy, but patterns of appropriation continue to a devastating degree. Today the world’s most popular household companies sell products tainted by forced child labour, but the disconnect between maker and user has made the labour of these 168 million children invisible.

Using individual photo transfers taken from a 1960’s geography schoolbook and displayed in an infographic format Jane highlights how information, as fact, is laden with subjective views of the world which is in a constant flux. Accompanying each photo transfer are charcoal and ink drawings of children at play with items produced by child labour to draw attention to this disconnect.

Matthew emery’s research box

This box contains work by Peter Kennard which was distributed in the form of a newspaper at his recent exhibition Archive of Dissent at Whitechapel Gallery. Kennard looks at the methods of control deployed by the UK/USA alliance to maintain global power. Emery does most of his research on YouTube, where countless documentaries and interviews with figures like Noam Chomsky and Franco Berardi can be easily found. He included this information in the form of links, rather than texts, to prove that sourcing unfiltered information and knowledge is accessible to anybody.

Finally, the box is made up of torn-down, fragmented sections of billboard paper, representing snippets of information that bleed through the lies the public are subjected to via mainstream media. The paper is made up of old advertisements that have been continuously covered with new ones, mirroring the way in which capitalism works and how misinformation is used to distract and control the majority. This is then spraypainted over and includes oil pastels to encourage viewers to leave their mark, inspiring autonomy and action.

Eleanor Street’s response

tl;dr

Eleanor Street

paper, cotton organdie, thread, ink, wood

75x40cm

Eleanor Street’s work tl;dr reflects on the democratisation of information through the self-publication offered by the internet and the consequences of this for trust, authenticity and reliability. She brings her own interest in materiality, layering and palimpsest to ideas around information, disinformation, obfuscation – and each individual’s own responsibility for how and what they consume. She considers the paradox that liberation from paternalistic management of information delivery and the subsequent wealth of information now at our fingertips, is undermined by its own provenance – because of growing evidence of malign actions by individuals and state actors; dishonesty and disruption in pursuit of clicks and monetisation; the collapse of trust in media platforms and figures of authority; and the evolution of AI. This paradox is reflected in the representation of digital information in a tangible, tactile form, evoking traditional systems of information ownership.

nele bergmans’ research box

This box contains the cornerstones of the material palette that Nele Bergmans uses in her sculptures and installations. Nele’s practice is based around the tensions that arise when materials are put together: the fragility yet rigidness of glass next to the softness and yet obvious hardness of stone pebbles. Through the juxta-position and assemblage of materials in their natural state and form, one can express feelings and thoughts that are beyond verbal expression, but that deal with the precariousness of contemporary life with all its complexities and

contradictions.

matthew emery’s response

Mule

Matthew Emery

Oil on card with handmade frame

70 x 86 cm

Through representation and a Cubist approach to perspective, Matty’s recent works respond to the complexities and the precariousness of everyday life under the control of Capitalism. At the time Picasso and Braque began to question form, Marxism was rising and workers believed in a future of hope and possibility, only for it to be shattered by war, power and hegemony. Many saw a future where technology assisted workers and labour eased, however capitalism utilised this power to further exploit the majority, making any sort of hope for the future appear futile. Mule is inspired by the laboriousness of working life, as portrayed in the writing Something for the touts, the nuns and the grocery clerks, by Charles Bukowski. It reads:

‘‘checkerboard days of moves and countermoves

fagged interest, with as much sense in defeat

as in victory; slow days like mules

humping it and slagged and sullen and sun-glazed

up a road’’

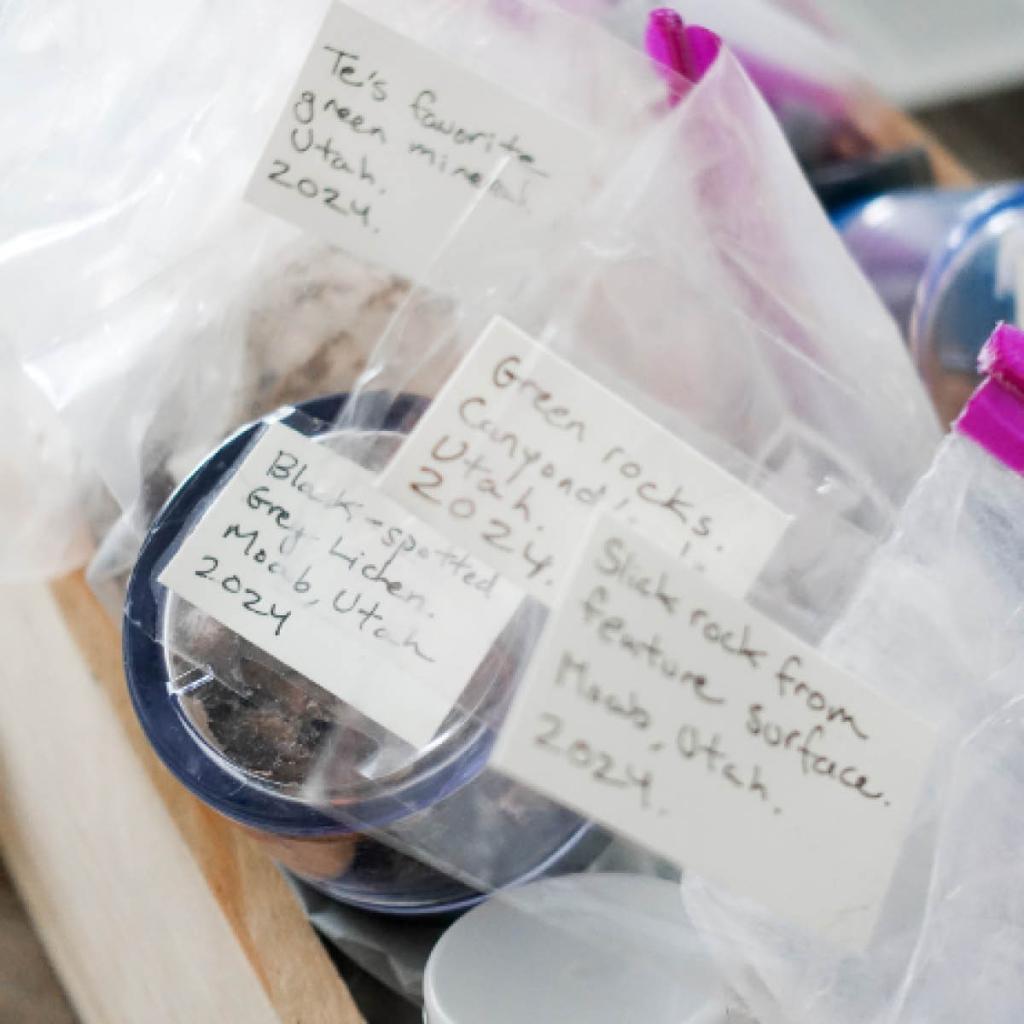

Te palandjian’s research box

From the mint green “Greensand,” to unidentified poops, to portions of Opuntia Ficus-Indica cactus skeletons, this curated assemblage of natural materials harken the heat, vastness, and vibrancy of desertscapes. Primarily, the collection focuses on plant and matter collected during Palandjian’s trip to Utah in Summer 2024, but in the interest of considering how different landscapes communicate to one another, also includes a few materials from trips to the Jordanian and Spanish desertscapes in 2022.

While “samples” from a specific place—like the shells children collect when they go to the beach, or a ceramic shard an archeologists bring back to the lab to carbon date—are often viewed as semiotic signifiers, reminders, or examples of the land it came from, Palandjian believes that samples from one place contain an energy and an agency to transform the new spaces they are placed in. To her audience and her artistic responder in South London, she provides a tool for bilocation, recontextualization, and desert-ly interruption.

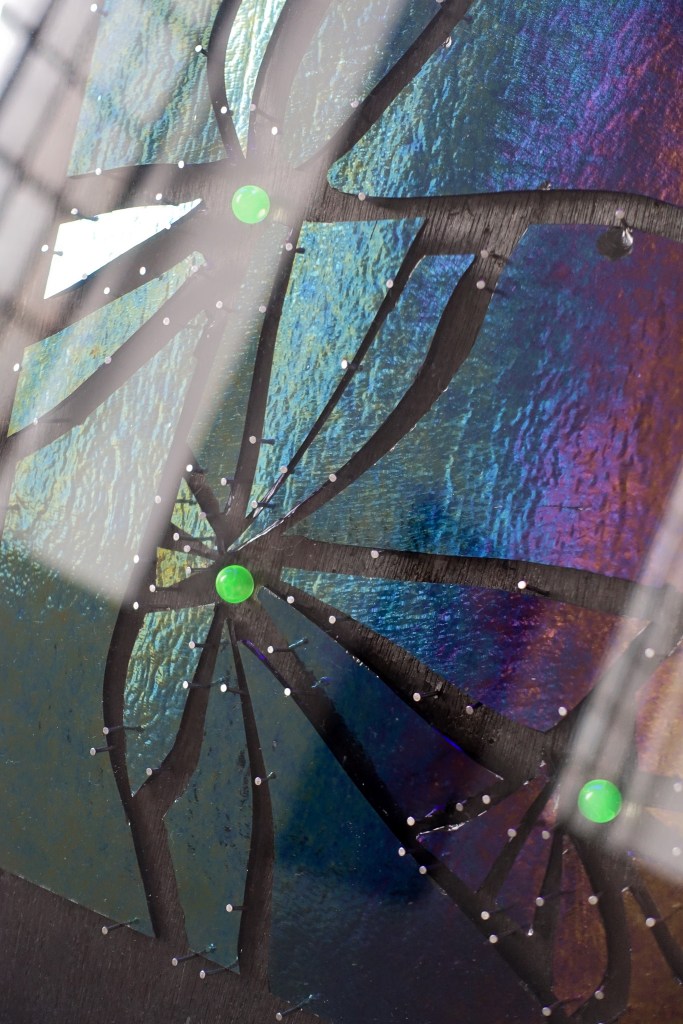

nele bergmans’ response

Moab, Utah and Jordan

Nele Bergmans

Steel, Perspex, glass, Uranium glass,

heat-treated plywood, UV light fixture

150 x 40 x 180 cm

Moab, Utah, is well known for its gorgeous and endless red sandstone canyon landscapes. When the settler Wiilliam Pierce saw the lands in 1880, he gave it the name Moab, referring to the biblical ‘land beyond the Jordan’, currently the East bank in Jordan. In 1940 the biggest national uranium reserve was discovered in Moab, enabling the US to expand their war arsenal with homemade nuclear weapons. When uranium is mixed in the glass mix (containing silicate, found in sandstone) you get a yellow/green looking glass that is UV reactive. In museums, vitrine-displays create a comfortable distance from the actual history, encountered as passive and fit in one curatorial narrative communicated through a short label. This work seeks to confront this tension: civilazations are actually being destroyed at this exact moment. The situating of objects into ‘archeology’ disrupts the possible engagement in the present.

By linking Moab, Utah with Moab in the Middle East, and juxtaposing the beautiful landscapes with the devastation caused by its mined minerals, this work exposes the contradictions and precariousness of contemporary life.

joy stokes’ research box

Within her practice Joy uses her body as a tool for mark making. She explores themes of health and disability and the grief surrounding loss of time. Within her research box is a series of seven drawings, one for each day of the week. They are a record of time, marking fluctuations in the swelling in her legs. Medical grade compression garments, medicinal anti-inflammatory gel and lymph pads are just some of the things that form the management of her chronic health condition. The box is made from two Lithograph prints made from the marks made by her body on a zinc plate.

Te palandjian’s response

Collective Dirt

Te Palandjian

2024, video

Participating in a Critical Edge show from abroad for the first time, Palandjian experiments with low-tech video art and text as substitutes for the landscape-adjacent objects she normally brings into the exhibition space. She considers: ‘‘What is dirt? And how can we behold it as much as possible?‘‘

carmen van huisstede’s research box

Carmen’s work researches the complex relationship between surveillance, power, and complicity. It reflects on how systems of surveillance and authority shape our attention, encouraging us to ignore inconvenient truths and suppress problematic memories. In a world of peer-to-peer monitoring and celebrity culture, not all forms of visibility are accepted—powerful elites can obscure their actions.

By reconstructing technological elements into sculptures, the artist aims to critique humanity’s obsession with documenting life over living it. Viewers are prompted to reconsider technology’s influence on perception. Transparency, even when assumed, can be distorted by the medium, raising doubts about visibility and the nature of information.

Joy Stokes’ response

Today, tomorrow, the week after next

Joy Stokes

Hosho paper, intaglio ink, cotton organdie,

thread, video projection

95 x 95 cm

Documented over a period of time, Joy’s artwork, Today, tomorrow, the week after next is a record of repeated actions. The importance of gaining knowledge and access to information, health care systems and building supportive networks, is at the core of this work.

With chronic illness can come a sense of lacking control as the illness takes charge of your body. Medical professionals seek evidence, from the patient and from tests. With Primary Lymphoedema, hospital checkups log progression in the condition, which can give a sense of powerlessness. This had led to Joy’s personal need to log changes. The compulsion to document our lives is a notion that can be seen in our increasingly surveillanced society where if we don’t have proof of something happening, does it even happen at all?

Invited guest artists

Jessica Brauner’s research box

Please turn the handle on the back of the box. You can touch the contents inside the box so long as it’s placed back when you are finished. Jessica Brauner’s research box marks a parallel to Pandora’s box: a feminine and macabre music box filled with the mythological and the monstrous. The box seeks to recall the sculptural work of Carolee Schneemann and the visual language of the video artist, Rachel Maclean. Inside the box’s openings you will find Shakespeare quotes, mythological fairytales, further artistic influences, a record of Jessica’s process, and Jessica’s thoughts surrounding

identity, video and AI.

Kate Kelly’s research box

The Boxed Library: Painting only in Ultramarine Blue, Phthalocyanine Turquoise and Titanium White, Kelly’s box represents the painters who have informed and influenced her practice. Using reclaimed wood and metal to create the external structure, Kellys box also references Lubaina Himid’s Man in a Paper Drawer, representing figures who have been hidden, and Kaye Donachie’s paintings of archived images of radical women of the early twentieth century. Kelly’s box represent all female painters. Some contemporary and some from the cannon, acting as her own personal archival reference, the scale of the paintings is reflective of a book.

Iliana Ortega Alcázar’s research box

Iliana’s ‘research box’ contains a selection of things that represent the journey she has been on recently in the making of a textile diptych. The journey involves engaging with ideas, concepts, texts. It involves experimenting and thinking about materials and processes. A key part of her recent research has been feminist thinking on home and diaspora, so her box contains snippets of a text by Avtar Brah. She has also included pieces of textiles, monoprints and materials used to make these, as well as imagery for a screen print, all of which represent her experiments with materials and processes.

Monya Riachi’s research box

Monya works in response to a context – which can be the geography she is in, an enduring

socio-political narrative, even personal archives. She works with materials as holders of meaning and embodiments of narratives. Monya is interested in themes around the politics of land, the entanglement of historical geographies, the measurement of time within chronocapitalism, and more broadly ecological transformation. Her research box at the moment includes maps of the Mediterranean, material experiments with salt and water, poppy heads, historical accounts of Britain in 1914, poetry by Mira

Mattar and Etel Adnan.

All photography by Nele Bergmans unless mentioned otherwise.